The Rube Goldberg Anti-Politics Machine: How a few thousand marbles could set off a chain reaction that determines a continent’s future

This quarter’s analysis starts with the troubling and growing wave of coups that have swept across the African continent, and this closes with the reason that I have hope for a stable, resilient, and prosperous future that hundreds of millions of Africans deserve.

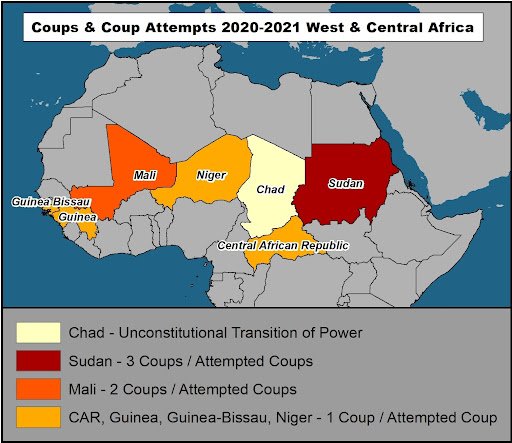

There was a coup in Sudan last week. It marked the ninth coup d’etats or coup attempt on the African continent since the start of the pandemic in 2020. More than half of the coups and attempts were in Sudan and Mali alone. In plotting these coups on a map, we see a contiguous line of coups and attempts that runs from the Atlantic to the Red Sea.*

This isn’t normal, and what’s worse: there are likely to be more. For context, this two-year period is at pace to be one of the most unstable time periods since much of the continent’s independence.** What is more concerning is that the majority of these coups or coup attempts are both still largely unresolved and concentrated in the same region.

Transitional governments have become the international community’s default solution to political instability in the region (as discussed here), but the transitional governments aren’t working because militaries aren’t relinquishing power. After decades of progress toward democracy, we could be seeing a return to military dictatorships on the African continent.

Authoritarian military regimes threaten to reverse decades of improvements in promoting a robust civil society and upholding democratic transitions of power; moreover, they tend to strengthen insurgencies that are plaguing the region. As fragile states further entrench themselves in protracted conflict, their scarce resources are diverted away from public services into security. With fewer public services, populations become more vulnerable to exploitation by Salafi-Jihadist insurgencies. Martial law makes sense as a narrative, but not as an effective strategy to defeat insurgencies.

The “Arab Spring” in the Middle East and North Africa offers cautionary lessons for sub-Saharan African countries.

What is now referred to as the “Arab Spring” was a series of mass protests and uprisings across the Middle East and North Africa in 2011. It brought an end to several longstanding and brutal military dictatorships across the Arab world. The most consequential global legacy of these events in 2011 was the start of two civil wars that have still yet to restore any semblance of lasting peace. The 42-year reign of Qaddaffi ended in Libya and thrust the country into war. While Assad in Syria was able to prevent his overthrow, he was not able to prevent civil war. The aftermath of conflict in Libya created a surge of weapons into the Sahel, and the conflict in Syria created a surge of refugees into Europe.*** In both Libya and Syria, groups like al Qaeda, ISIS, and their affiliates flourished in the power vacuums created by conflict.

The warning signs are present now, lest history repeat itself. Each state, in pursuing its own individual national security and stability, may set off a chain reaction of popular protests that result in a second wave “Arab Spring” that would spread not only across North Africa as it had in 2011, but also to large portions of sub-Saharan Africa that are much more fragile now than they were ten years ago.**** If we focus on individual coups and coup attempts as stand-alone events, we miss the bigger picture. Similarly, attention is paid to specific elections due to the fear that a potential spark could ignite a powder keg region into turmoil. Focus is placed on trying to identify and extinguish points of ignition, but very little to diffuse the bomb. The number of potential sparks are increasing, and the blast radius is expanding, and soon.

Evidence of this can be seen in the international focus disproportionately given to next month’s election in the tiny riverine nation, the Gambia.***** Slightly smaller than the Bahamas, the Gambia had just over 500,000 people vote in their last presidential election–that’s fewer people than the population of Las Vegas, Nevada. Rather than using a more conventional ballot system for elections, the Gambia is internationally unique in its use of marbles as the means by which voters cast their votes. The use of marbles as a ballot has proven effective in establishing inclusivity of illiterate voters. However, the upcoming elections are likely to be highly contested, and the use of marbles as a ballot opens the elections up to allegations of fraud or tampering. These allegations could spark violence–a form of violence that is likely to set off a chain reaction in neighboring countries, sparking further unrest. The Gambia’s geographic location in the heart of Senegal risks that violence spreading. Up until now, Senegal has been able to largely remain stable and keep a Salafi-Jihadist insurgency at bay. In fact, the only area of potential risk is in a small part of southern Senegal–the same part of the country that is divided by the Gambia.

“…the high number of political parties participating in the election [20], coupled with The Gambia’s first-past-the-post electoral system, means that a candidate with just 100,000 votes [marbles] can become the country’s next president.” (Aljazeera)

Geography matters. On the surface, the presidential election in a tiny country shouldn’t have a significant impact globally. One more coup in Sudan, the country that has had the most coups in Africa, shouldn’t carry with it significant global consequences either,******* but it is the regional and global context in which these events take place that makes them have the potential to set a continent ablaze in conflict. Mali, Chad, and Sudan******** all have transitional military governments. The transition from authoritarian rule (as discussed here) is particularly perilous. With all three in the same region, they are almost stacked like dominos. All too often, the top-down policy stops at the national level, failing to link with bottom-up solutions that address populations vulnerable to insurgents.

“the domino effect” by Kurt:S is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The transnational Salafi-Jihadist insurgents that are now ever-present in discussions of Africa north of the equator will not be defeated without the support of the marginalized and vulnerable populations whom they exploit. Military transitional governments and dictatorships that lack legitimacy from their populace are ruling with borrowed time. Popular protests as seen in Sudan, Mali, and Chad expose a rift to drive a wedge that insurgents can exploit.

“Insurgency is a competition between insurgents and the state for the support of the local population.” – David Galula

The Nuru model reinforces fragile states where they are weakest–remote, rural areas. These are the populations that policy doesn’t reach and where the state often is losing the competition with insurgents. Our work brings communities back together again after they have been torn apart by conflict. The Nuru Ecosystem achieves gains in agricultural productivity, expands access to digital financial inclusion, promotes healthy behaviors, and builds rural businesses. By bringing communities together around common economic interests, the Nuru model helps to restore livelihood strategies, revitalize income streams, build resilience to shocks and stressors, and ultimately link communities to local governments and the regional economy. To ground this Q3 analysis with a tangible example, I wanted to share a brief experience of how I was humbled by the transformative cumulative impact of Nuru Nigeria’s work.

I was in northeast Nigeria in August 2021, in part to formalize Nuru Nigeria entering a grant agreement with USAID. I took part in celebrating a deepening US engagement with Nuru Nigeria’s work. While there, I had the honor of witnessing first-hand the impact of Nuru Nigeria’s work on building social cohesion. However, closing out this same week, I couldn’t stop scrolling the news from Afghanistan following the US withdrawal there. The juxtaposition of engagement and disengagement–cause and effect–was clear. The lively communities I visited in northeast Nigeria, once destroyed by conflict and largely displaced, were filled with traditional music, song, and dance that hadn’t been performed since before the insurgency. The resilience of rural people to restore their lives is what gives me hope. If rural communities in northeast Nigeria can determine their own future, one not controlled by the will of Salafi-Jihadi movements and Boko Haram, then I can also find hope and stand resolutely by the sides of marginalized people in the vulnerable communities of northeast Nigeria and the greater Sahel.

* I have also included Chad on this list because, while it isn’t officially being categorized as a coup, the President, Idris Déby, was killed and his son assumed the country’s leadership despite it being unconstitutional. For more details, refer to last quarter’s blog.

***Weapons: some estimates have 75% of Libya’s weapons ended up in the Sahel. Refugees: while exact statistics are difficult to pinpoint (somewhere between 800,000 to 1.2 million), Germany alone has taken the most Syrian refugees in Europe.

****Arab Spring

*****Aljazeera

******ElectionGuide

*******Sudan has had 17 coup d’etats

********Even after the coup, Sudan is already working to reestablish a transitional government.