As many industrialized nations begin to emerge from the COVID-19 global pandemic and reopen their economies, much of the rest of the world is still reeling as mass vaccination remains out of reach. At the time of writing, less than 1% of the total population of the continent of Africa has been vaccinated (NYT) In addition to the human toll, the virus has had widespread economic and political ramifications. Most, if not all, of the countries in Africa find themselves weaker now than a year ago, while violent extremist organizations like Boko Haram and Islamic State have become stronger. A period of even greater instability should be expected.

Over the past several months, I have been asked directly by a number of donors and NGO colleagues about some of the developing geopolitical and security challenges we are seeing, not just in Nuru’s areas of operation, but more broadly in the countries where we work as well as various regions of the African continent. As a result, on a quarterly basis, we will start publishing a brief analysis of a few of the trends we are seeing. For the sake of brevity, these updates will only provide a brief overview of a few of these trends and do not reflect the full scope of our analyses. This quarter will focus on Ethiopia and Chad.

Why Ethiopia and Chad?

What makes each of these countries important right now is that they are both in different stages of transition from long-standing authoritarian leaders, Meles Zenawi and Idriss Déby, who provided regional stability at the expense of domestic human rights. These types of transitions are often a long, difficult road with most routes leading to violent conflict emerging within 10 years of the transition.* The primary challenge with transitions from authoritarian rule is the balancing of competing sources of legitimacy that any successor needs to navigate.**

- The old guard: the power base associated with the authoritarian regime;

- The rebels: the regime (or dynasty) that was displaced (or underrepresented) by the last regime that often lives in exile;

- The international community: the international support that the previous dictatorship enjoyed and that allowed them to stay in power;

- The people: the groups marginalized under the previous regime who often have long-standing grievances and abuses.

Ethiopia and Chad are each approaching their transition differently. I summarize the strategies as: Ethiopia using “the rebound,” and Chad using “the cooling off period”. The stakes for both are exceptionally high. Each leader needs to balance popular will for reform and demands for democracy*** while in the process avoiding removal by either the old guard or rebels, and also sustaining international support.**** Too much reform loses the old guard, while too little reform is accompanied with crackdowns on protests and riots (to maintain order) benefits rebels. If either strategy fails, then further instability will spread and enable extremists to spread into these two states and further destabilize regions. To put things into perspective, the fall of Gaddafi and the subsequent proliferation of weapons is directly linked to the instability in the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin still a decade later.*****

What’s Happening In Ethiopia? “The Rebound”

The “rebound”: a short-term uncontroversial leader used as the transition before another potential long-term leader assumes leadership.******

The multitude of political and societal challenges that Ethiopia is facing cannot be overstated. As mentioned above, transitioning from authoritarian rule is often a violent and non-linear path. Would-be reformers can quickly emulate and even exceed the transgressions of their predecessors as they try to plot a course for a unified country amidst heavy division. In 2021, Ethiopia finds itself in a political balancing act of ethnic competition for power (with mass atrocities and reprisals);******* potential regional conflict;******** and heavy pressure for social reform from the populace.******

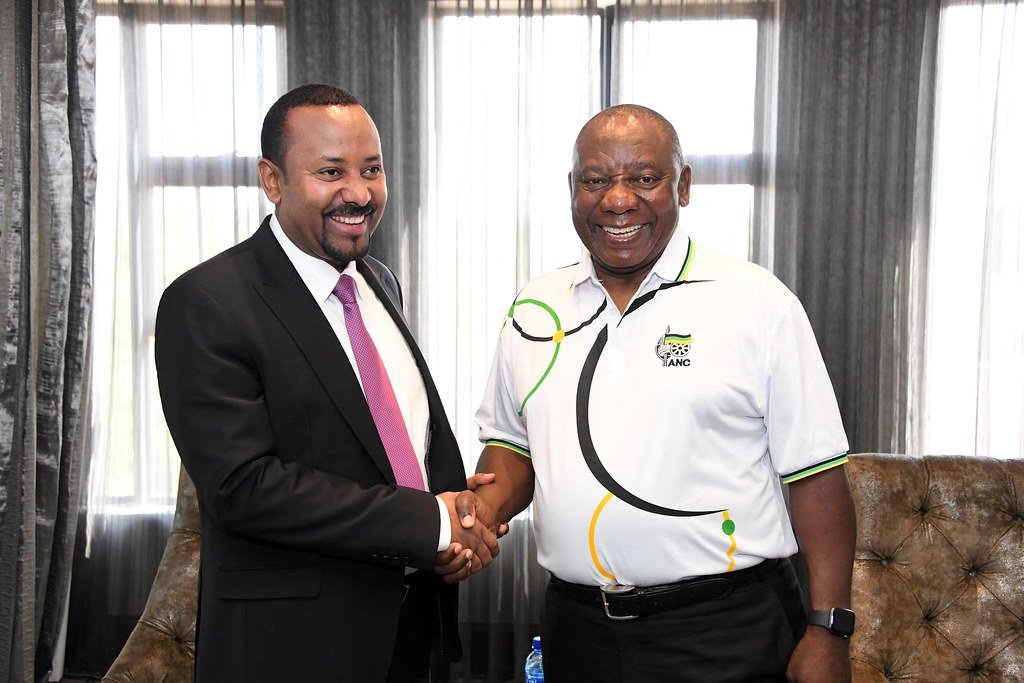

Ethiopia’s upcoming election in June is the culminating event to track. The Ethiopian government has traditionally used the threat of a common enemy at their borders to unify the country (typically Eritrea and Somalia). Prime Minister Abiy’s success in improving diplomatic relations with those neighbors is a double-edged sword. While it removed a key source of legitimacy that was a legacy from the old guard as defenders of Ethiopia against those popular enemies, it also limited his ability to achieve that defender status in that same way. Without that unifying tool at his disposal, Abiy’s actions to unify will likely be made manifest through exhibition of strength and control internally rather than projected externally.

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) and its scheduled second filling in July is best understood using this lens. While controversial internationally (particularly with Egypt and Sudan), the GERD’s symbolic significance for the government of Ethiopia is equally paramount domestically, as a crowning achievement toward industrialization and electrification. The reported atrocities in Tigray and the designation of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) as terror groups should also be seen through this lens of unification against a common enemy that Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed is defending against. While effective in the short-term, should the fighting endure, it will hamper any potential for future power-sharing. It may also lose him international support.

Photo Credit: “President Cyril Ramaphosa hosts Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali on Official Visit” by GovernmentZA is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

Even in the exceptionally likely event that Prime Minister Abiy wins the election in June, domestic ethno-political tensions only make up one part of the challenges that he will face: growing cases of COVID-19 and the resulting economic impact caused from a pandemic; a resurgence of last year’s locust swarm; and what appears to be the beginning of a long fight against several insurgent groups. It is unclear how effective the rebound strategy has been for transition. The old guard has been displaced, which opens up some opportunity for reform, but it is unclear if fighting insurgents will prevent that reform from occurring.

An excellent panel discussion that gives an overview of the current situation can be found here.

What’s Going On In Chad? “The Cooling Off Period”

The “cooling off period”: a military government that will transition to civilian rule and elections after 18 months.

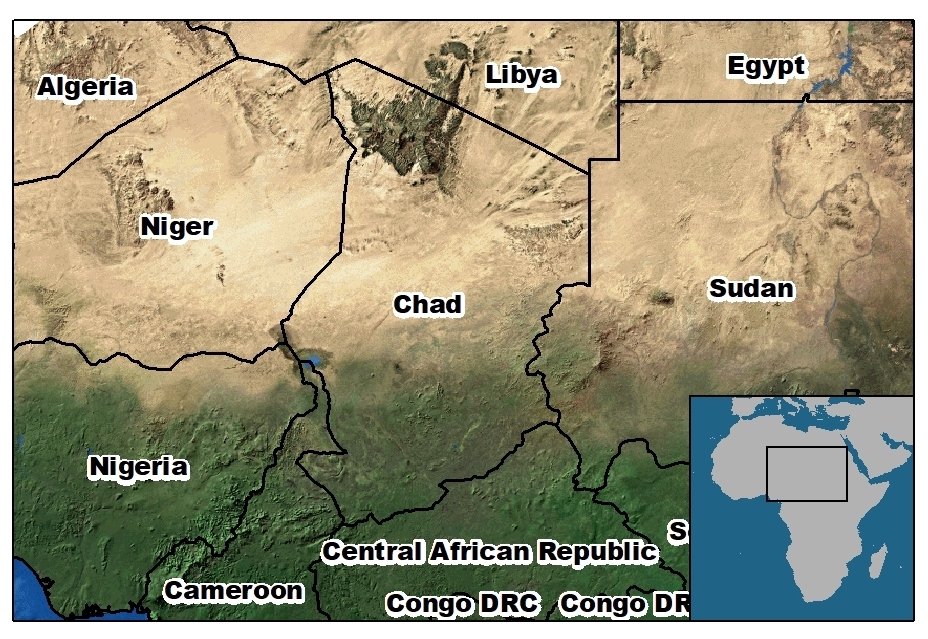

President Idriss Déby’s recent death (April 19, 2021) has sent shockwaves throughout both the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin regions. Déby has been a regional strongman for the past 30 years. Chad plays a critical role in counterinsurgency operations throughout the region and has been a key ally for both France and the US. Immediately following his death, concerns began emerging in the international community because Déby and Chad have had such a strong stabilizing influence in the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin.********** Now the country may need to step away from its role in regional counterinsurgency operations to focus on its own domestic stability.

To frame this in a geographic perspective, Chad shares borders with Libya to the north, Darfur (Sudan) to the east and the Central Africa Republic to the south. Its remaining neighbors to the west (Niger, Nigeria, and Cameroon) and the Boko Haram insurgency may be its most stable border. Chad has been a pocket of stability in the midst of an array of insurgency challenges in the countries surrounding it. Interestingly, there have been virtually zero calls for democracy or following the mandates of the Chadian constitution from the international community. In fact, France recognized Déby’s son as interim President despite the lack of adherence to constitutional protocols. In stark contrast, Chad is seeing protests and calls for democracy and elections internally. Given nearby Burkina Faso’s rocky transition from authoritarian rule and the spread of extremists, the preference for stability over domestic legitimacy through democratic elections is understandable from a regional and international perspective.*********** A chief difficulty for the new president of Chad will be navigating the catch-22 of legitimacy via international support alone (France).

Chad’s domestic political realities are particularly Chadian. More leaders have come to power in Chad via coups than elections. A very small group of elite families with a high degree of interrelatedness form several competing rebel factions. A number of the coups foiled by the former President Déby were from his own cousins. The new President Déby is coming to power in a way that some are characterizing as a coup backed by the French. It is still unclear whether Déby has the support of his father’s old guard. The 18-month transitional Chadian government is inheriting multiple conflicts, both foreign and domestic. The more this successor is seen as propped up by the French, the more resonance the narratives of violent extremist organizations (like ISIS) will have in characterizing the move as neo-colonialism.

Questions arise regarding whether the allure of power will tempt the rebel elites to throw in their lot with extremists as Tuareg nationalists did in the 2012 Malian coup. Will domestic pressure from within France force the French to reduce their support for the new President Déby if he is particularly repressive or doesn’t transition power? Regardless of the answers to these questions, the even larger looming questions are, what will this new chapter of leadership mean for both the Chadian people, for Chad’s relationship to other regional governments, and for the myriad insurgencies looming along the borders of this country? The answers to all of these questions will be revealed in time, but it is important for our team and partners to stay aware of how this leadership transition progresses, especially in light of our plans to scale in the Sahel region and our current operations in NE Nigeria near the border with Chad.

Two excellent analyses on the current situation in Chad can be found here and here.

Concluding Thoughts

Why does this matter? Ethiopia plays a crucial role in providing stability in the Horn of Africa. It has the second largest population in Africa, and it is the headquarters of the African Union. Chad plays a crucial role as France’s partner providing stability in the Sahel. Both countries diverting their attention to domestic stability creates a gap in each region at a time in which violent extremist organizations have been emboldened. Having situational awareness of challenges like these that are being faced by people living in these regions will help us all continue to partner more wisely and effectively together to cultivate lasting meaningful choices in the most vulnerable and marginalized communities in the world.

*Notable examples include: Gaddafi – Libya; Habiyarimana – Rwanda; Compaoré – Burkina Faso; etc.

**While somewhat dated, given its focus on post-Cold War transitions, Guillermo O’Donnell series on “Transitions from Authoritarian Rule” is still incredibly relevant to what seem like universal challenges occurring in these types of transitions.

***Which will outpace the state’s capacity and willingness to change and lead to increased social pressure in the form of protests, riots, etc.

****Who may turn their support to the old guard, rebels, or the people

*****Gaddafi was overthrown in 2011 as part of the Arab Spring movement. At the time, Libya had one of the most well-armed militaries on the continent. Gaddafi had a long history supporting Tuareg rebels and employing Tuareg mercenaries. After the fall of Gaddafi there was a surge of weapons and Tuareg fighters that flowed into the Sahel and NE Nigeria. Tuareg rebels allied with al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb to throw the 2012 coup in Mali.

****** Short-term relative to the predecessor with no real prospects of assuming the role long-term leadership of the country. Meles Zenawi died in 2012. He had no real successor. Prime Minister Hailemariam was inserted by the ruling party (the old guard) to lead the country until his resignation in 2018. He didn’t come from any of the major ethnic competing for power and was out of the country during the war (which has been a source of legitimacy for Meles and as well as Abiy).

*******Tigray losing power and fighting to maintain it; Amhara vying to restore previous power and exact reprisals; and the ethnic majority Oromo vying for representation and exact reprisals.

********The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) and its potential to affect the flow of the Nile and Egypt’s Aswan Dam has been a source of ongoing friction between Egypt and Sudan. Sudan has also had a series of attacks on Ethiopian citizens in disputed border regions. Both have the potential to escalate.

********* Lockdowns due to COVID-19, a state of emergency, rapid inflation, crackdowns on protests, widespread regional violence against civilians and a delayed election have all led to increases in social pressure for change.

********** It is worth noting that while President Déby was a powerful ally to French, US and UN forces in their counterinsurgency efforts, he actively destabilized the Central African Republic in their ongoing civil wars.

*********** It appears that Chad is following the transitionary government strategy similar to that of Mali and Sudan, but, given that those all three of transitions are set to complete in close sequence, it may open up a new array of risks.