In hard times throughout human history, coming together has provided a path back to normalcy, to solidarity, to stability. When our communities are torn asunder by disease, conflict, civil strife, gaping economic divides, religion, ethnicity, or any number of factors, how do we find a path back? How do we find a way to overcome the things that divide us and emerge to talk, to convene, to sing, and to dance in unison?

How do we find unity?

Social scientists use the term “social cohesion” to gauge and measure relationships. While there is disagreement on the exact definition, the principal dimensions are 1) a reduction of disparities, inequalities and social exclusion and 2) strengthening of social relations, interactions and ties. (UNDP) Essentially, we can achieve a high level of community cohesion by breaking down those things that divide us, and building the networks of relationships to be able to come together.

In academic literature, this can sound abstract and far-fetched. Even in daily life, where the looming spectre of the COVID-19 pandemic still hangs over us, finding ways to come together can even sound like a bad idea. So again, I’m left with the question–in the face of high obstacles and looking at such monumental challenges to come together–how can we move forward not just as individuals but as communities, as societies?

My thinking was jarred by a recent trip to northern Adamawa State in northeast Nigeria. I had previously visited this community market center in November 2016. That particular journey was my first visit to Nigeria as part of initially establishing an intervention and organization there. The community had for a time been overrun and ravaged by the Boko Haram insurgency the year prior in late 2014 into early 2015. The few market stalls were ransacked, pocked with bullet holes, and the roofs were blown off. Only about a third of the populace was still around. Most of the fields lay fallow. The armed forces securing the greater area still had bans on growing tall crops, so farmers were only allowed to cultivate crops short in stature, lest the tall crops hide malicious insurgents.

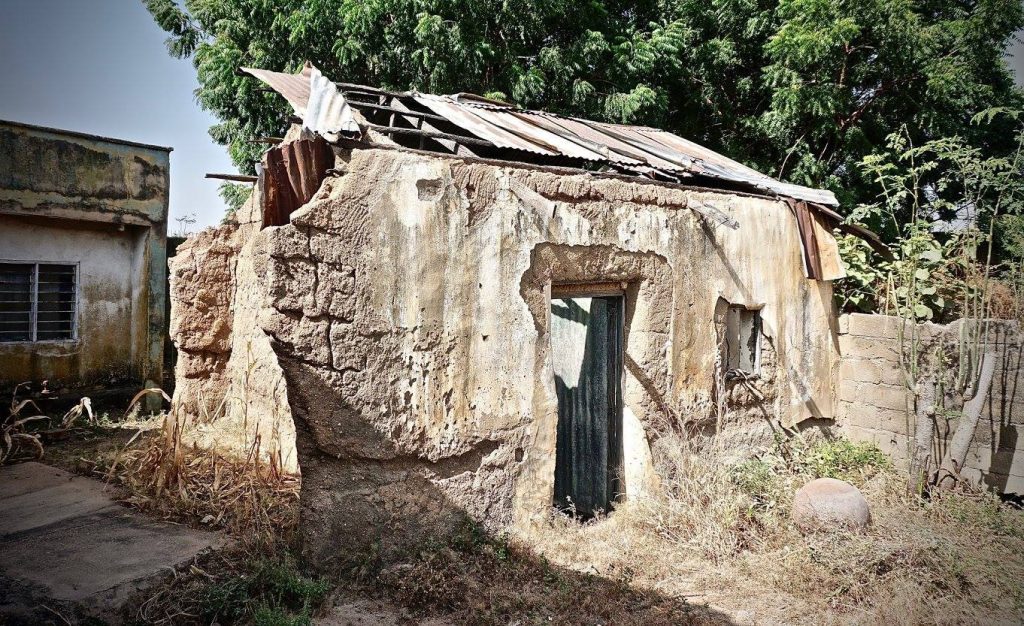

2016 destruction at the hands of Boko Haram

I had little in my life experience with which to compare this 2016 visit. This once vibrant community, a place still inhabited by hopeful and resilient people, looked like a ghost town I had once visited in the western US. The experience left me with a gnawing uneasiness in my stomach. The hollowed-out village setting belied just how much of normal life was absent from this place.

Even at that time, I made it a point to not dwell on what was missing, but rather I made the concerted choice to focus on energy and hope. In the face of complexity and challenge, how could Nuru work with these communities to overcome despair and inaction? How could we contribute and partner with strong community leaders to identify prudent ways to help build back on more solid footing? It would be no easy feat.

Lasting Impact

The immediate physical, psychological, social, and economic costs of the insurgency’s impact were staggering, estimated at up to $9 billion. But the most insidious part of conflict is its stigma.

Like a stain that refuses to wash out, the damage from conflict has been long-lasting. Structures have been rebuilt. Infrastructure–key bridges, water sources and electrical grid were destroyed–and have been slowly recovered. Other aspects of life have yet to return to normal. The population of largely smallholder farmers has only slowly regained the physical security, resources and willpower to come back and rebuild their livelihoods. Gradually, as a sense of security has returned and farmers were able to leverage resources, they slowly built back. But there remains grinding desperation in the populace to restore what they once had – a robust and considerable livelihood. This still seems frustratingly out of reach. The psychological toll has been particularly long-lasting. Trauma is individual, collective, in the subconscious, and–in this environment–is assumed to be present.

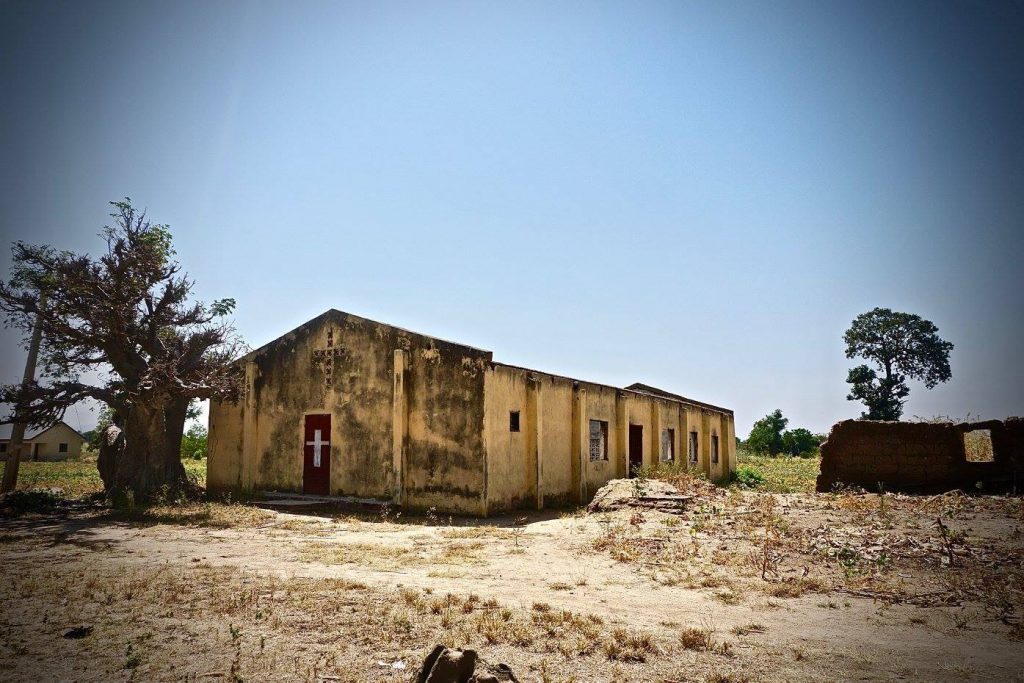

The biggest and most transformative changes have yet to take place, which would build a path to restoring stability and future prosperity. Brick and mortar banks, once established and thriving in town, are still vacant. Economic activity tends to be seasonal farming – rather than deeper investments – because more fixed investments could become subject to theft and targeted pillaging.

The Sights and Sounds of Coming Together

And what about social cohesion? After an enduring conflict, which persists in the region, and amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, economic crisis, ethnic tensions, political divides, and so many other potential dividing factors has the community come back together? Or is social cohesion a persistent casualty of conflict?

This leads to the biggest surprise of my return to this village center in August 2021. With the enterprising nature of the community, the assistance of the state government and non-governmental organizations, the market center has been rebuilt. Many of the village occupants have returned. What had been empty and desolate just five years before, the market center was now bustling. The fields leading up to town, once largely abandoned and fallow, were now planted with crops right up to the roads and homesteads. A scene that once held the eerie and abnormal silence–not even the bleating of goats to be heard–was now filled with the sound of life. This was the most dramatic change of all.

As we pulled up to the market center, there was a joyous outpouring of traditional song and dance–a revival of cultural traditions. The traditional community leader, near tears, delivered a heartfelt speech in the local language. This whole scene was hardly what I expected. I traded words with my local colleague to glean some insight. What was this whole scene about?

More Than a Dance

The community had not been able to celebrate in this way for over seven years, since before the Boko Haram insurgency. Youth were experiencing–for the first time–traditional cultural practices, traditions, and music that would not have been possible or allowed under the rule of insurgents. Boko Haram would have preferred to continue preying on this community, pillaging their crops, stealing their girls, and destroying their assets. In a sharp rebuke to the future that Boko Haram would have wanted, this community celebration was an act of defiance, a choice for the future, and a declaration of their independence.

What I witnessed in this community was social cohesion beginning to take shape. I was proud that Nuru International and Nuru Nigeria contributed to this transformation. Through our efforts to restore farming livelihoods and rebuild household and community economies, our organizations helped farmers come together around common economic interests. We’ve always believed that shared economic interest is a key engine for enabling greater social cohesion, but what we experienced in Nigeria demonstrated that people can come together and heal and rebuild in ways we had never imagined, like through dance and traditional cultural songs and ceremonies.

As we departed the event to continue on field visits, the local musicians started into their fifth tune. The party had just gotten started. It was an honor to see the outward signs of healing that were beginning to manifest through coming together. We are all so lucky to have witnessed a glimmer of how coming together is part and parcel of healing ourselves and our communities. In answer to my question about how to overcome hard times, what I learned in Nigeria was that finding the courage and strength to convene and celebrate is a fundamental part of restoring normalcy and stability.