Burkina Faso | Hope Can’t Stand Alone

My background in international conflict analysis shapes how I approach my role as CEO of Nuru International. I monitor trends with my team and identify geographies where our combined experiences and backgrounds can help vulnerable communities stabilize and chart a path forward to resilience and prosperity. We serve communities like those in northeastern Nigeria who are trying to rebuild and reunite after living under the Boko Haram caliphate. When we started Nuru, we intended to take our approach into some of the most challenging places in the world. There are many groups that are making meaningful contributions in the fight to end extreme poverty. For Nuru, we have always been about going into communities where others are much less likely or less willing to go. I’m proud to announce that we have officially launched efforts in Burkina Faso, and I would like to explain how and why we are continuing to push the boundaries of work. To understand where we’re headed, it helps to understand where we have been and built a track record of success.

Forging New Centers of Hope in Northeast Nigeria

Nuru International exited our third country, Nigeria, in June 2022. Four years ago, when we started working in northeast Nigeria, we were told it was a lost cause. It was too risky, too violent: “Why build something for someone else to burn?” We were repeatedly advised to focus instead on stable places. This is the problem. Poverty is concentrated in fragile states. Whole regions often get branded with the label “conflict areas” or “fragile.” ((https://nuruinternational.org/blog/nuru-views/quarterly-geopolitical-analysis-4/)) Overly broad labels create a stigma that ultimately leads to a self-fulfilling prophecy as entrenched marginalization festers and instability grows and spreads. Nuru Nigeria’s work stands resolute as a counterfactual to this conventional narrative.

In a record time of four short years, we were able to start and build a best-in-class local organization, Nuru Nigeria, and increase crop yields by 291% and income by 770%, while surpassing scaling targets. This was all accomplished in an area with an active insurgency that was formerly under the Boko Haram caliphate. We have watched divided communities in the northeast begin to come together and reclaim their identities to become more than “conflict areas” or “former caliphate communities”. They are forging new centers of hope and prosperity.

Others are taking notice: USAID and GIZ have each invested in Nuru Nigeria’s success and have started funding scaling to new communities. Nigerian foundations are also investing, including multiple years of funding and renewals from ACT Foundation. Nuru Nigeria is gaining both local and international recognition for its achievements. Nuru Nigeria’s Managing Director, Amy Gaman, was just featured in Newsweek. For these changes to begin to take root, particularly in uncertain times and circumstances, we have to first sow seeds of hope. This is where Nuru International comes in.

Standing Far Away – Burkina Faso’s Ill-Fitting Label

As we prepared to launch operations in Burkina Faso, we heard many of the same narratives that we heard about northeastern Nigeria: “It is a lost cause”; “It is too dangerous to work”. Similarly to northeastern Nigeria, we saw the same self-fulfilling prophecies beginning to take shape as funding dwindled and organizations left. We see remnants and reminders of organizations that used to work there, but have left.

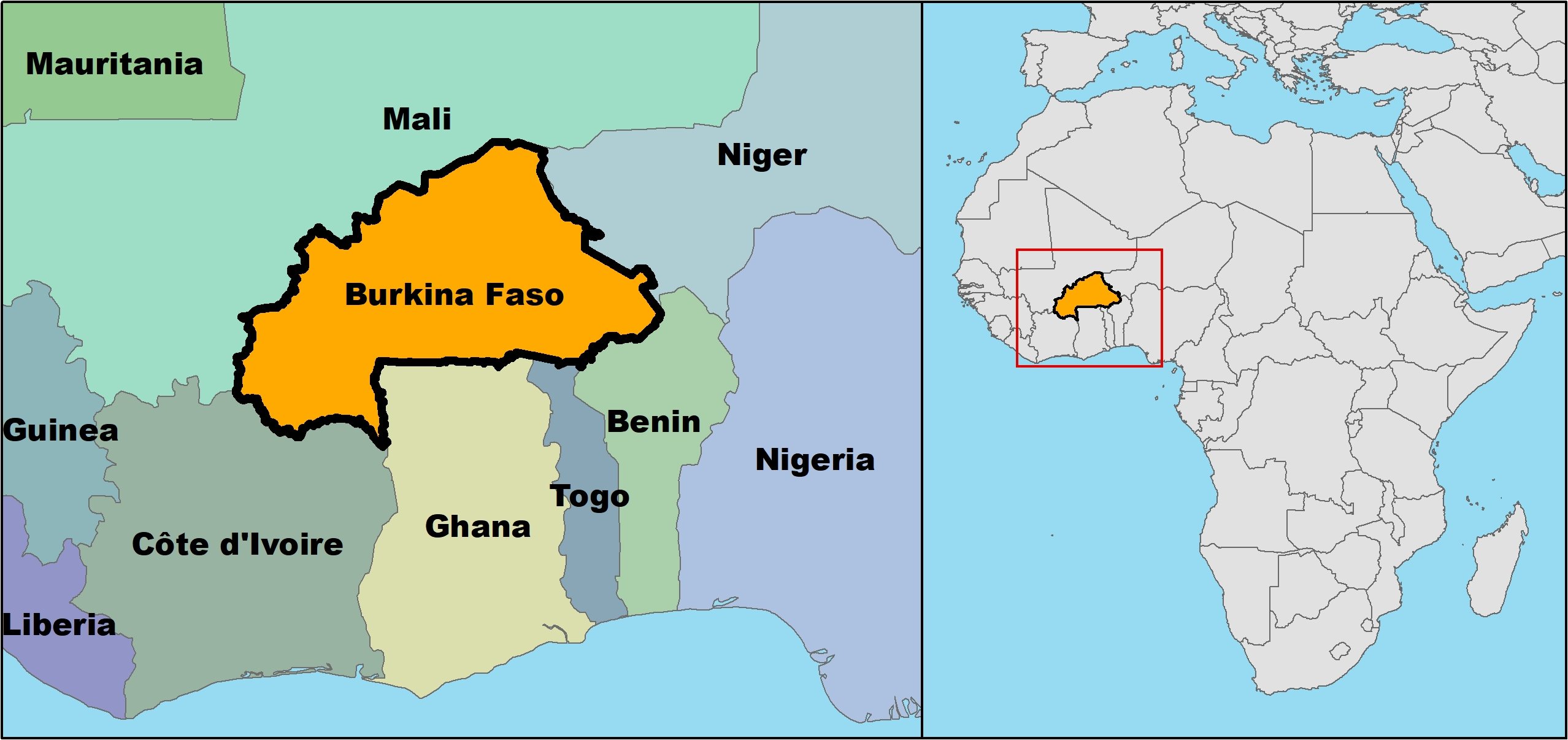

On the surface, it makes sense: Burkina Faso has, in the space of a few years, quickly descended into becoming one of the most violent places in the world. The US State Department has it on the highest risk travel advisor: “Level 4 – Do Not Travel”. The UK travel advisory map shows the whole country as red, apart from a tiny dot in the capital. These rankings and maps neither paint an accurate picture nor tell the full story of a nation. We, at Nuru, believe that there is power in proximity.

You need to get close to understand what’s really going on, so that you can begin to comprehend the lived reality of the communities that we aspire to serve. I know close.

Getting Close – Serving in Burkina Faso

You need to get close to understand what’s really going on, so that you can begin to comprehend the lived reality of the communities that we aspire to serve. I know close.

I served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in northern Burkina Faso. I lived with the Fulani, an ethnic group made up of nomadic herdsmen, in the Sahel Desert. This experience framed and shaped my understanding of poverty. My service gave me the briefest glimpse at life with your back up against the wall and nowhere to go.

Aerie Changala serving in Burkina Faso

My first week in our village, locusts decimated the crops. I thought, “It can’t get much worse.” Then, I got really sick–I lost 70 pounds in a handful of weeks. It can’t get much worse. Drought starved the livestock of their food and water, which ultimately resulted in total loss of livelihoods and savings for the herdsmen and their families. It can’t get much worse. Then came famine and disease crept in, stealing the lives of both the young and the old. It got worse.

I was wholly unprepared for daily loss at that scale. Life and death on the edge of northern Burkina Faso entirely reshaped my understanding of the real burden, the scourge, of extreme poverty. Watching the desert grow as the sand came in like the tide across the fields, I remember speaking with some of our village elders and asking, “Why can’t we just move?” They were nomads. Couldn’t we just go somewhere else? Wasn’t there somewhere with food? Couldn’t we go somewhere with water? Their response still acts as a reminder of how simple problems can look from afar, but it isn’t until you get tangible and granular that you appreciate their complexity.

“Where? Tell us where we can go, and we will go. We aren’t welcome anywhere.”

As a twenty-something-year-old Peace Corps Volunteer coming to terms with disaster, drought, disease and death, I finally understood the gravity of life with no good options.

Extreme poverty not only means fewer choices. It means only having bad options. Do I pay to take my sick child to the doctor or do I use that money to feed my family for one more day? Do I sell my dying cattle (my entire savings) at unimaginably low prices or do I risk one more day, hoping for a drop of rain or a spot of grass to sustain them? Do I try to eke out one more day on the edge of the desert or do I look for greener pastures, knowing that it could mean conflict?

A Critical Situation

Nearly two decades later, the situation has worsened still. Our village, for all intents and purposes, no longer exists. The area where I lived is now the new epicenter of global terrorism. The place that I once called home has been gutted of its population, and my friends and old neighbors are gone. The Fulani, my former gracious hosts, have been cast as the villains in the media narratives that seek to explain how Burkina Faso became violent so quickly.

Context:

- Burkina Faso currently ranks second globally for civilian deaths due to terrorism and hosts more political violence than Syria, Iraq, and Somalia. Only Afghanistan ranks higher. Swaths of the population are internally displaced people–refugees in their own country–cast out by violence from their once peaceful homes and plunged into new depths of vulnerability as they precariously carve out a new means of survival. Whole parts of the country are being gutted, emptied of their populations as they become safe havens for insurgents.

- Burkina Faso also ranks in the bottom ten globally on the UN’s Human Development Index: “The UN’s measure of social and economic dimensions of a country are based on the health of people, their level of education attainment and their standard of living”. ((https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human-development-index#/indicies/HDI)) This means there is precious little capacity for the rest of the country to host their internally displaced masses, even as they bear out an escalating insurgency.

By only looking at these indicators, it would be easy to dismiss Burkina Faso as a lost cause. It is not. Pessimism and fear would have us falsely believe failure and disaster is inevitable. By only seeing Burkina Faso as an extremely poor and extremely violent place, a critical factor is missed: the Burkinabé people themselves.

Burkina Faso’s Strong Social Fabric

Burkina Faso has the highest level of social cohesion on the African continent. The term ‘social cohesion’ reflects a level of trust shared among a group of people as well as a belief in the fairness of and a connectedness to their governing systems. Social cohesion is a strong indicator of the glue that keeps a country together. To put the significance of their ranking into further context, Burkina Faso also ranks much higher than the US. ((https://solability.com/the-global-sustainable-competitiveness-index/the-index/social-capital)) Burkina Faso is a country with tremendous grit and heart.

As a tangible example of what social cohesion looks like in practice, we can look to the process by which Burkina Faso renamed itself and its people. Casting off the former colonial riverine reference name of Upper Volta and forging a new identity that cemented a lasting union of its people in their shared home, Burkina Faso drew inspiration from all three languages of its major ethnic groups. Burkina Faso aptly means “the land of upstanding people”. The country is teeming with so much social fabric that it manifests in a literal national fabric (Faso Dan Fani) that represents its people. Even now, despite an active insurgency and a military coup, the Burkinabé people have tremendous pride in and love for their country.

Woman weaves Burkina Faso’s national fabric (Faso Dan Fani)

A Complex History of Challenges in Burkina Faso

If Burkina Faso is so united, then why is it so poor and violent? The answer is complicated and reflective of compounding challenges. While it’s impossible to fully unpack here, a few key factors have significantly contributed to the struggles we see today. First, shrinking pastures due to climate change combined with growing farmlands due to population growth means that nomadic herders have less land to graze their animals and therefore face a threat to their way of life (and existence). Herders, in this case the ethnic group called the Fulani, are predominantly Muslim, while Christians make up the majority of the farmers. What starts as a competition over limited resources can quickly become an ethno-religious conflict. These fights historically have been very small skirmishes with people armed with swords. The Arab Spring (2010-2012) that led to the fall of Qaddafi changed that. Some experts cite that 75% of all of Libya’s weapons ended up in West Africa following the fall of Qaddafi. Groups like al Qaeda and ISIS have exploited Fulani vulnerability to radicalize and arm them to spread violence in the region.

The region in the north that was once my home is now gone. Groups like ISIS and al Qaeda have exploited the vulnerability of desperate people to make safe havens. They will continue to expand through exploiting the vulnerable and destabilizing regions. This is not solely a Fulani problem. Extremists will continue to prey on the vulnerable and marginalized to grow. When we started Nuru, we did so because we knew the exodus of choices that follows conflict. Someone needed to intervene in a way that could bring long-term stability. Someone needed to come alongside communities and equip them with the tools, knowledge and resources to chart a lasting path toward hope and meaningful choices. Nuru was built to be that “someone”–to serve in places like the Burkina Faso of today, to stand with them to build a better tomorrow. The charge of finding a place for building hope is a call to action that guides our work at Nuru to this day.

Nuru International Impact and Learning Director Casey Harrison facilitates demo plot training in Burkina Faso.

Now is the time to act. Now is the time to invest in building the resiliency of the vulnerable communities in Burkina Faso who are fighting to hold on to the priceless values and way of life that are built into the fabric of their society–represented in the physical tapestry that represents the Burkinabé people. They have been clinging to hope, but hope can’t stand alone.