What is La Niña?

La Niña is a weather pattern coinciding with colder than average waters in the Pacific Ocean, affecting global weather events and climate. During La Niña years (2020-2022, 2016, 2008-2009), normal weather patterns are disrupted, leading to intensified storm activity in some places and droughts in others. In North America, the Midwest, the northern Rockies, Northern California, and parts of the Pacific Northwest experience above-average precipitation. By contrast, the US southeast and the US southwest, including southern California, experience decreased rainfall.

La Niña also contributes to a more active Atlantic hurricane season, which runs from June 1 to November 30. In South America, La Niña drives drought in Peru and Chile and above-average rain in Brazil. La Niña contributes to flooding in eastern regions of Australia. In Asia, it drives above-average rainfall. And in Africa, La Niña typically contributes to increased precipitation in southern Africa and drought in East Africa.

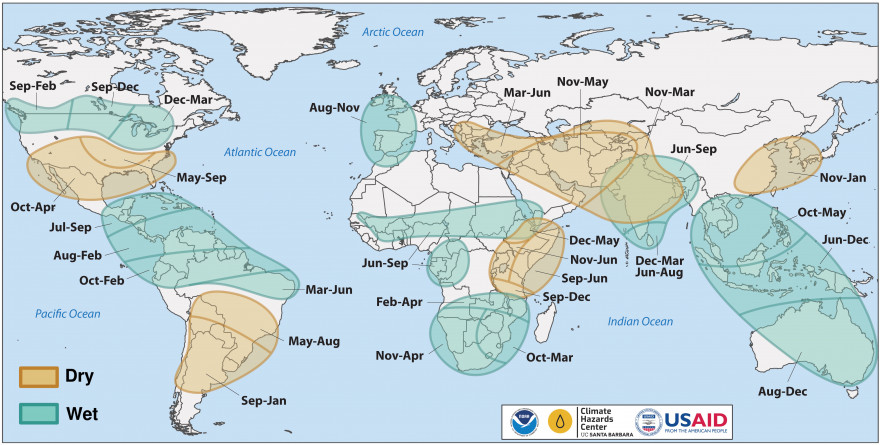

Timing of wet and dry conditions related to La Niña.

Global Impact of La Niña

El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), the term used to describe these recurring climate patterns, has a major influence on rainfall and the complex interaction between the ocean and atmosphere. Typically, there is a phase change around every one to three years, varying between the cold La Niña phase and the warm El Niño phase. No two El Niño and La Niña phases are alike. They are unique and hard to predict. Large-scale pressure changes are observed with each new phase which affects circulation patterns over the rest of the world. Understanding medium-term climate cycles, like La Niña, means we can better predict and prepare for weather events in the future. However, this effort to predict ENSO-related weather events is becoming increasingly difficult as increased greenhouse gas emissions make ENSO events even more variable. This further highlights the importance of slowing climate change and improving predictive modeling (Nature).

The impacts of La Niña go well beyond isolated weather events. Cool currents in the Pacific Ocean contribute to altering weather around the globe, and their impacts can last for several years. The consequences of unpredictable and extreme weather events can send shockwaves that reverberate loudest in the most vulnerable corners of the world. Predicting, preparing for, and responding to the impacts of aberrant weather events matters. As a global community, we’ve learned that events that start out small and isolated can quickly snowball to impact everyone. For example, take the emergence of a novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China, or the outbreak of hostilities in Ukraine. Seemingly isolated events can have far-reaching consequences.

Farmers on the Frontlines

The latest wrinkle in the 2020-2022 La Niña phase has been its contribution to driving drought in the East African countries of Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia.

As I’m writing this post, farmers would typically be looking at their fields with set grain and even harvesting some early-maturing crops. Instead, many farmers are looking at a failed harvest of brown and withering crops. June is also the longest time period since the last harvest. For farmers who rely on the harvest for their income, this is the time of year when their personal food supplies are stretched thin. In a good year, waiting for crops to mature in June is a difficult wait; in a bad year, it can be downright agonizing. 2022 has been a trying year in more than one way for smallholder farmers across sub-Saharan Africa.

The COVID-19 pandemic is still ongoing on the African continent, and the vaccination rate remains low. Supply chain disruptions globally and locally have contributed to price spikes across key commodities. This includes manufactured products and critical farming inputs from global suppliers, as well as basic food commodities like Ukrainian wheat as well as fertilizers. Inflation is increasing and spiking. Within this context, the prospect of a looming drought in East Africa as of June 2022 is set to have an outsized negative impact. This matters to the rest of the world because reduced food supply and agricultural productivity can drive conflict and fragility that spreads and permeates.

When I wrote about El Niño in 2015, I observed: “The effects of El Niño and La Niña have broad-reaching effects on global weather, but they penetrate even further into the global society and economy. In countries like Kenya and Ethiopia, 80% of people are smallholder farmers and often live hand-to-mouth. Setbacks on crop yields, food security, and income caused by climate events, like a drought or flood, means economic household recovery may take not days or months, but years.” I echo my call to action today, some seven years later: “Government, communities, and civil society are not yet equipped or resilient to take on the challenge alone. It thus becomes a global imperative to assist.”

Our Role Amid La Niña’s Impact

Amidst compounding challenges in 2022, I find cause for hope and optimism. By focusing on lasting meaningful choices and locally-led development, Nuru helps communities regain their agency, advocate for appropriate policies, and adapt to increasingly variable weather-related shocks. Nuru Kenya, for example, has a decade-long history of promoting climate-smart and regenerative practices. These good agricultural practices are adopted slowly, season to season, as farmers gain confidence in their effectiveness to increase their yields and incomes.

Our work at Nuru International embraces a holistic approach to community climate resilience in partnership with locally-led organizations of the Nuru Collective. In essence, our collective strategy is to promote locally-led climate adaptation:

- Regenerative agriculture: Nuru Nigeria employed professional soil testing to help rightsize farm input packages and fertilizer applications that help farmers achieve more profitable production while offsetting negative environmental impacts in the soybean value chain.

- Increased income and financial inclusion: Nuru Kenya helps farmers diversify their livelihoods into dairy production and irrigated tomato horticulture, contributing to income gains and helping farmers to weather the shock of drought.

- Food and nutrition security: Nuru Ethiopia is promoting mung beans – a crop with a short maturity period, high protein content, and stable market value.

- Agribusiness professionalism: Nuru works with farmers through cooperatives. These for-profit businesses benefit members and help them weather hard times. In Kenya, participating cooperatives offer an outlet for above-market sales of milk. In Ethiopia, cooperatives serve as a communal grain store and bulk buyer, selling back grains to farmers during the lean season.

- Community-based dialogues: By bringing farmers together through cooperatives and encouraging discussions on natural resource management and gender dynamics, they can pool their effort, address common challenges, and cope with tough times together.

To deal with the specific threat of unpredictable weather events, Nuru International also brought on board an innovative partnership with Ignitia. Rainfall in the tropics is highly localized and not readily predictable by climatological models developed for temperate regions. Ignitia delivers hyper-local, highly-accurate weather forecasts for the tropics. In partnership with Ignitia, Nuru is broadcasting daily, weekly, and monthly weather forecasts via SMS text messages in the local language to farmers in rural northeast Nigeria and in Burkina Faso.

Our collective impact intends to foster resilience in households and communities to prevent the worst weather impacts and to avoid cascading negative consequences for families, communities, and nations.