The Fall Armyworm (FAW) Spodoptera frugiperda began its swift expedition–the initial outbreak–across Sub Saharan (S.S.) Africa in 2016. By the end of 2017 it had devastated maize fields in over 20 countries. Nuru first chronicled our experience with the FAW outbreak early last year and the fight continues. According to the FAO, 37 countries in S.S. Africa have detected and officially reported FAW incidence in 2018. In a little over two years FAW has spread from a field in coastal Nigeria to farmer fields across S.S. Africa leaving a trail of lost maize, sorghum, rice, and millet yields in its wake. FAW has put a new stress on the small profit margins smallholder farmers depend upon to pay school fees, cover health clinic visits, and invest in their own entrepreneurial ventures. FAW is a new threat amongst the myriad of external risks that have the potential to keep hard-working rural households across S.S. Africa trapped in a cycle of extreme poverty.

One of the biggest challenges to FAW control during the 2017 outbreak was consistently communicating timely and actionable information to smallholder farmers at different stages in the maize growth cycle. FAW has an accelerated life-cycle that generates new infestations of mature “hungry” worms every month. The short life cycle and lack of freezing temperatures allows for multiple FAW outbreaks during a single production cycle of maize and other grain crops.

Early planting was no defence against FAW for this “knee high” maize plant in Kenya in early March 2018

The health of the maize plant is highly vulnerable to FAW early in the growth cycle, before it reaches knee high height. Moreover, if there is a spike in FAW populations late in the maize growth cycle (as cobs begin to form) the worm can bore deeply into the maize stalk or cob greatly damaging the valuable grains before they are ready for harvest. The omnipresent nature and ferocious appetite of FAW in the warm weather of S.S. Africa requires the delivery of consistent, timely and accurate information to smallholder farmers. That information allows them to apply safe manual and chemical controls at the time they will be most effective in protecting their livelihoods.

Remaining Vigilant Amidst Fall Armyworm

Nuru spent significant time and resources to build systems that would generate that type of information for farmers in Ethiopia and Kenya. Rural livelihoods teams developed action plans and coordinated with national partners to adapt activities that would deliver the latest scientific and locally actionable solutions to Nuru farmers. Led by local staff and informed by farmers from Nuru-supported farmer organizations (FOs), Nuru Kenya (NK) and Nuru Ethiopia (NE) updated agricultural training and extension strategies with new integrated pest management (IPM) practices, organized the distribution of appropriate pesticides and personal protective equipment (PPE) for farmers, and developed agile FAW monitoring systems that deliver actionable extension information to farmers.

For example, in Ethiopia we worked with local staff and their farmer networks to develop a Farmer Action Monitoring System (FAMS) for FAW. FAMS for FAW uses smartphones, easy-to-use software and local community extension agents to generate analytical resources, in local language, that generate FAW control plans that are appropriate for each farmers field. The Nuru-supported FOs mobilize hundreds of farmers to combat FAW across their shared landscape, which is necessary for long-term mitigation of negative FAW-related impacts.

Nuru Ethiopia Data Entry Clerk Tewodros Dawit using a smartphone to record FAW damage to maize during the testing phase of FAMS for FAW in November 2017

In February of this year, NK mediated meetings between agricultural input companies and Nuru-supported FOs that led to a suite of collaborative activities, including knowledge sharing, technological demonstrations, and the distribution of promotional materials for effective FAW controls. The benefit of having Nuru as facilitator and mediator is that farmer agency and well-being remain a high priority in these types of meetings. The NK rural livelihoods team views the trust of their farmers and FOs as a precious commodity, and through continuous engagement ensures that the least harmful pesticides and proper health and safety standards are part of all training and extension delivered to Nuru farmers. It is the trust built through good and bad times that increases the willingness of Nuru farmers to adopt new technologies and practices.

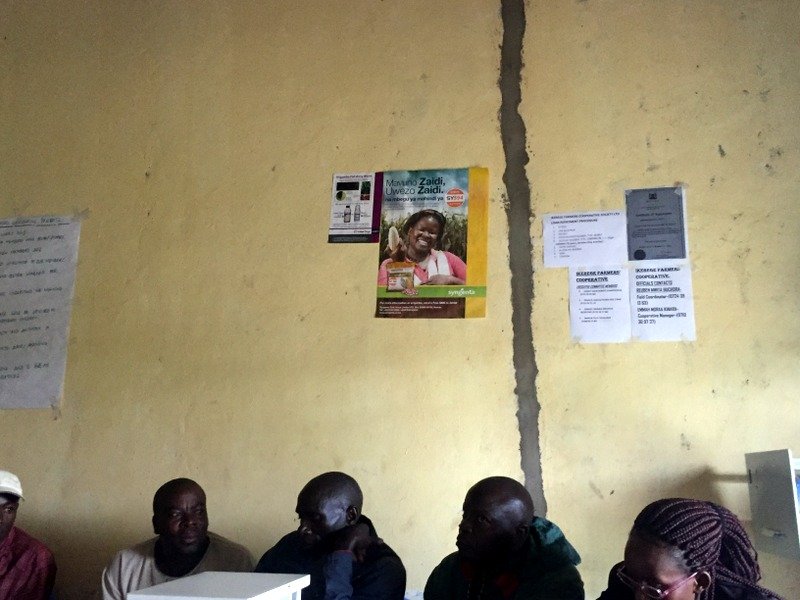

Ikerege Farmers Cooperative displaying promotional materials for hybrid seed and high quality FAW pesticides on their office walls, during a visit in March 2018 we discussed health & safety strategies and the importance of “chemical rotations” to combat FAW resistance

Collaborative efforts were mobilized in Ethiopia as well. In March, the NE rural livelihoods team visited a large-scale irrigated maize farm in Kucha woreda (county) to assess reported outbreaks of FAW. FAW was detected in the field. The investigation was intended to jump-start FAMS for FAW and behavior change communication efforts in the NE operating area, but it was also part of a coordinated effort with woreda and regional government partners. The visit confirmed that FAW was a 2018 threat to farmers in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR). The NE team immediately communicated this realization to government partners.

Alemseged Lukas, Berhanu Gumara, Tekalign Teferi and the NE team discuss FAW characteristics in order to confirm FAW presence in Kucha Woreda, March 2018

2018 Outlook | Fall Armyworm

International and local experts, led by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (UN-FAO) and preeminent agricultural research institutions, galvanized a rapid collaborative effort to generate technical guidance for smallholder farmers in Africa to control FAW in 2018. Nuru has found this guidance invariably informative in adapting our training curriculum and extension guidance for Nuru farmers. However, even the experts have acknowledged that local knowledge and local experiences are integral to building resilience to FAW in rural communities. Co-creating solutions to the most pressing challenges in rural S.S. African communities is a Nuru specialty.

The risk that FAW poses to 2018 maize harvests across S.S. Africa remains high. The Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI) estimated that the economic impact from 2017-2019 puts between $2.48 and $6.19 billion USD at risk of being devoured. This loss of value will disproportionately affect smallholder farmer profits and household income. Household income that is vital for sending their children to school or to purchase malaria medication during the rainy season.

There is good news from the field. Strong early season rainfall in Nuru operating areas has slowed the spread of FAW, but Nuru farmers remain vigilant and well prepared to monitor and control late season outbreaks. Farming is risky business and farmers know this better than anyone. Heavy rainfall that slows FAW can quickly turn into floods that erode soils and destroy crops. There is no “silver bullet” to manage FAW, or the myriad of external risks that threaten rural profits in S.S. Africa. That is why Nuru believes farmers are the most important agents of change and our co-created development interventions aim to prepare them to navigate the rough road from vulnerable to resilient rural livelihoods.