Ever wonder what your life would have been like if you’d taken a different path—like skipped out on college and started your own business? Married your high school sweetheart? What if you could turn back the clock and experience what life would have been like if you’d made other choices? In the Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) world, we set up experiments that let us see this alternate universe.

To gain clarity on the events, contexts, and experiences that make us who we are today, M&E practitioners administer baseline studies. In other words, to understand change and the causes of change, it helps to know where you started (with a baseline). Baseline studies attempt to answer the questions:

What would have happened to me if I had done “x” – and how would my life be different?

Specifically, Nuru M&E provides objective assessments of impact programs to drive data based decision making. We rely on baselines in particular for two main purposes: 1) to establish comparability between Nuru farmer households and non-Nuru farmer households (ideally the groups are the same at baseline); and 2) to provide a starting point for future follow-up surveys geared towards drawing conclusions about impact. Practically speaking, the questions help us understand if Nuru farmers’ lives have improved because of Nuru programs.

In the nonprofit sector, not all programs traditionally receive baseline and follow-up surveys. Using Financial Inclusion (FI) programs as an example, M&E teams and program stakeholders typically track individual level financial data via deposits, withdrawals and repayments on loans rather than household level survey data. These financial data demonstrate behavior change in savings and loans management. However at Nuru, M&E seeks to demonstrate how this financial behavior change results in longer term impact. Ultimately, we’d like to know:

How does Nuru Ethiopia Financial Inclusion help Nuru farmers mitigate adverse economic situations?

To understand this, we completed our first step: a baseline survey.

In support of Nuru Ethiopia Financial Inclusion (NE FI), M&E performed a baseline of the first group of Nuru farmer households and non-Nuru farmer households in 2014 (Baseline 1 or B1). In anticipation of NE FI scaling in 2016, M&E also baselined a second group of Nuru farmer households during 2015 (Baseline 2 or B2). The baseline surveys collected data on farmers’ involvement with savings, loans and income generating activities (IGAs) as well as coping mechanisms.

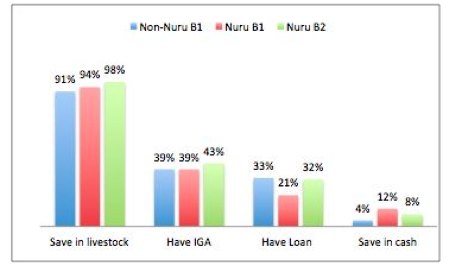

First and foremost, the findings confirmed that both the intervention and comparison groups share similar characteristics at baseline. In other words, this means that Nuru M&E can draw conclusions about the impact of the NE FI program in future follow-up studies. Specifically, in terms of savings behaviors across the intervention and comparison groups, farmers display comparable savings patterns at baseline: most farmers save in the form of livestock (non-financial savings) rather than in cash (Figure 1). Moreover, relative to cash savings, more farmer households engage in loans and off-farm IGAs.

Figure 1: Percent of Households With Livestock, Cash Savings, Off-Farm IGAs and Loans

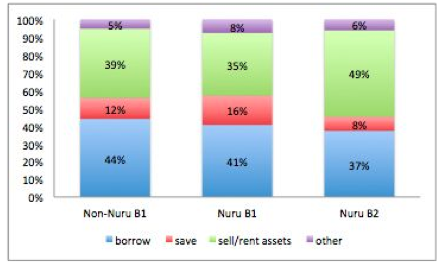

Additionally, for the first time, M&E analyzed data on farmer households’ ability to alleviate shocks. The findings show us that farmer households across all baseline groups turn to similar coping mechanisms to deal with adverse situations: most farmer families employ risky strategies such as borrowing from a neighbor or family member or selling or renting their assets (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Most Common Coping Strategies for Farmer Households

Moving forward, NE FI will aim to help farmer households rely more on sustainable coping mechanisms in the event of shocks like a family illness, the loss of livestock or a drought. Through increased cash savings and access to loans as well as income generating activities, Nuru farmer households should be able to more easily mitigate these challenges over time.

Given the findings, M&E identified several areas where NE FI could leverage the evidence to tweak program design during the initial phase of implementation. Some of the questions and suggestions for NE FI include:

- Consider incentivizing farmers to save in cash through livestock IGAs: Increasing financial (cash) savings is a core part of NE FI’s goal. Since farmer households favor non-financial savings in the form of livestock, can NE FI incentivize farmers to save in cash more frequently via offering livestock income generating activities?

- Explore other barriers to cash savings: The data highlight farmer households’ reluctance to save in cash. Can NE FI explore these obstacles to cash savings and work on helping farmer households overcome them?

Several lessons emerged from the NE FI survey for Nuru Ethiopia M&E as well:

- Shorten the survey: Farmers expressed frustration at the length of the survey. Moving forward, M&E will work in conjunction with FI to shorten the survey and prevent survey fatigue.

- Clarify cash savings versus in-kind savings (livestock) survey questions for enumerators: Working with financial concepts across cultures can be tricky. In the future, M&E will improve the survey training in order to reduce illogical inconsistencies that appeared in the baseline findings.

All in all, the baselines generated lessons for both M&E and FI. Concurrently, the findings established the foundation for measuring if Nuru farmer households cope effectively with economic shocks and essentially have a more secure financial future. Stay tuned for updates from the upcoming follow-up FI survey in Q2 of 2016.